Little else can make you appreciate the United States like spending 2 years in Africa. A nation of so many thoughtful and practical individuals, individuals of soaring vision and ambition, with an unshakable belief in the importance of a basic level of fairness. Americans have a lot to be proud of.

And yet—it doesn’t make me proud to say—we are profoundly bad dancers.

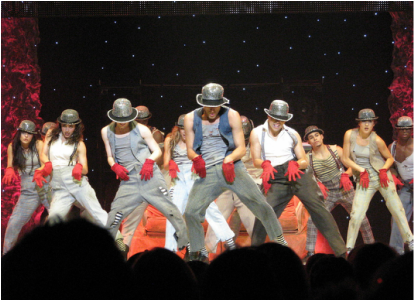

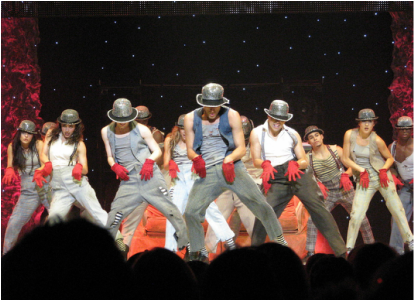

But wait, what about these people? But wait, what about these people? Sure there are exceptions, most notably these dance specialists we train to become spectacularly good at dancing, then make movies and TV shows about. But it seems to me that that’s just America covering a weakness (dancing) with one of its most formidable strengths: we are really, really good at producing individuals who are really, really good at a thing. Of course some sub-cultures in the U.S. perform better than others, but as a herd of people I’d say, we’re pretty bad dancers. In any group of 20 random individuals, probably no one is winning any awards. In the U.S., the word party doesn’t even necessarily imply dancing, which is strange enough by the standards of a lot of countries. A good chunk of those dancing at the party are wondering if they’ve put in enough of an appearance on the dance floor to be mercifully allowed to sit down. In a world where people go to discotheques, Americans go to clubs. I think at the heart of the problem is this idea that the thing about dancing is whether you are good or bad at it. In countries where almost everyone dances really well, the thing about dancing is just that people really love dancing. It doesn’t occur to people that they might be dancing well or badly, it just occurs to them that the next song has a really…good…beat…I think that how well a culture dances is an indication of how comfortable people feel in their own skin, and how unselfconscious they feel. It’s about losing yourself in the music and shutting off your higher brain. Americans tend to be more cerebral and self-conscious. I’m sure I’m overstating the case a bit here, but the fact remains that America is not a place with a strong dance culture, or more generously, whatever dance cultures that do exist are very fragmented. Mozambique stands in contrast. Its culture is one of extreeeme unselfconsciousness, and not surprisingly people here are good at dancing. Most Mozambicans I know have been losing themselves in the joy of dancing regularly from a very young age. And so, I want to use this post to show off some of the cool dancing that pervades the region. And now, here are two videos that make me happy. :) The first showcases a bunch of moves that are typical in Mozambique. This video should give you a good feel for the style of dancing you’d see if you went to a party in Mozambique (party = dancing!). The musical style is called marrabenta, and it’s definitely popular in Mozambique by its own right.

I wish I had videos to show from parties I have personally been to where we would see dancing almost as good as in this music video above, but trust me that people know how to move like this all over. The same goes for this second video, but I gotta say these kids are reeeally good—a cut above the rest. The musical style is Chinguere, and the music and the dance have roots among the Shona people of neighboring Zimbabwe. At a typical party in Chimoio you’ll see people dancing like in both of these videos depending on the song, plus a few other styles. There is a big emphasis on footwork in general, I’d say. There is also a more generic style of dance I commonly see here that I can only describe as spiderlike.

I want to end with a disclaimer: these dance generalizations about Mozambique probably don’t apply to a lot of the folks up in the northern regions of the country, where I understand dancing isn’t permitted in the Islamic communities.

Anyway, I hope you enjoy the videos as much as I do. Until next time!

A picture is worth a thousand meticais. Or something like that. Here's a look around my home-away-from-home, Chimoio!

And just like that, 5 months go by! Yikes, where did the time go? I have been so intensely here that it has been hard to think about anything outside of this place. Life here, and especially work, has been my whole world these days. Tunnel vision. My non-Mozambique memories seem like other lifetimes. Really. It’s unsettling. I feel like I arrived at 22 years old last September like a typical Peace Corps Volunteer, and turned 30 last month.

Having written that, I see that returning to this blog will be very good for me. Time to take a big breath, step back, and reflect a little bit on the last half-year. I thought it’d be nice to start with this picture of me with these giraffes! That was a few months ago. A family of wild giraffes inhabiting a reserve about 40 km outside of Chimoio. So beautiful and so majestic. I was with a group of other PC Volunteers, and we all actually involuntarily cried out when we saw them, if you can believe such a thing. It always fills me with awe to see a big animal like this in its natural environment.

So what have I been up to for the last half-year? I have been busy. Like, stupidly busy. The main culprit is the university where I work, UCM--Universidade Católica de Moçambique. Chimoio is home to UCM’s engineering branch campus, so the focus here is on the more technical disciplines—civil engineering and food chemistry may be the two cornerstone programs if you had to pick. That said, our Chimoio branch also offers degrees in things like business, law, and clinical psychology, so don’t ask me what that’s about. As an education PC Volunteer, my main deal here in Mozambique (my “primary project”) is teaching. But already that’s where my experience departs from the norm. My enormous challenge/responsibility/opportunity is that this semester (which began in February of this year) is the first semester of the first year of our electrical engineering department’s existence. And the department is me. We have about 55 students so far, each paying a lot of money to attend this university, and they have chosen our brand-new electrical engineering major. I was a little shocked when I arrived in December of last year to learn that nobody had been hired to bring up the program that would be opening in 2 months, that the university was gambling pretty hard on their new foreign volunteer and his broken Portuguese. I probably would’ve been a lot more shocked to learn that the same is true over 6 months later, today.

But tudo bem, savvy readers will remember that this new electrical engineering department and the opportunity to be a professor of engineering is exactly what drew me here in the first place! It’s been a difficult semester, but still I wouldn’t rather be anywhere else. I wanted the chance to make an impact and to work at something that matters, and here it is. I’ve had my butt kicked by jobs that I believe in and jobs that I don’t, and I can tell you which I prefer. What’s incredible about my post is that there seems to be an endless of amount of really great work to be done, and the only limit is the amount of time and energy I can put in. Such boundless opportunity, for me, has been a ruthless taskmaster. It is a pit into which I throw so much time, effort, and caring-about-things but can never seem to fill. And if that seems like a really negative way to describe my first 6 months here, well, it’s been a tough semester.

How do you create a university undergraduate program? I sort of panicked for a few weeks at the beginning, but eventually developed a strategy. I’ve been fumbling through it. There was a lot of trying to remember what my old college courses and labs were like. Any program needs a curriculum and professors, and hugely important for electrical engineering are labs and a ton of technical equipment. And these are the things that I’ve been worrying about since I arrived. An immense stroke of fortune is that UCM has money to put towards the program, and we’ve been making good use of that so far. Here’s a short summary for the main things:

Curriculum – It’s no small task to marry a strong electrical engineering program with relevance to the actual jobs in Mozambique and to the knowledge base of available professors. I’m still taking it one semester at a time!

Staff – When I first arrived, the university president asked me to head the department in the official role. But I felt and still feel that it would be better aligned with Peace Corps goals (and my goals) to have a Mozambican do this, with me assisting that person. The president was very understanding and we agreed that we would hire a department head. We eventually interviewed candidates for this job and tried hiring someone, but it didn’t work out; he wasn’t able to commit to full-time work and had to leave after a week. I’m still the only person on staff and have been doing more of the department head stuff than I’d like, but I’m extremely grateful that the physics professor and civil engineering department head have been helping out a lot. The hiring of a motivated and capable EE department head remains probably the single most important thing for my service here to have been a success.

Lab – I’m very excited about this! I’m posting the official “before” picture below. Early on I drew up a layout for the lab and I’ve been working with the local carpenter on the furniture (lab benches and such). We’re about 1/3 of the way there. UCM has an electrician on staff, who’s been great, and I’ve been working with him a lot too.

Equipment – This, more than anything, has been an insane undertaking. So many hours of research. I’ve ordered dozens and dozens of unique pieces of equipment/tools/material, in large quantities, from U.S. businesses and local where possible. It’s a start, and there is much, much more to go! See picture below.

Then there’s teaching. I began the semester slotted to cover the main EE course for semester 1, Introdução a Engenharia Eletrotécnica, plus teaching Inglês I for the engineering students. Several weeks in though, I discovered that two additional classes were in need of professors, and I began teaching those too--Inglês I for night students and something called Oficinas Gerais. It’s a long story, and I don’t have the heart to tell it. It was too much. None of these classes have curricula or textbooks, except for whatever the professor can get her hands on. This semester I made 18 MB of PowerPoint slides in Portuguese for Introdução a Engenharia Eletrotécnica, our class notes. I don’t have another semester like this one in me. It was way too much, and by the end I felt more defeated than accomplished. There is a lot going well at UCM, really a lot, but there are planning and scheduling challenges unlike anything I have ever seen.

I first tried this blog entry a week ago and just couldn’t do it. It’s been a hard semester, and not in a way that has felt very poignant or poetic or has made me feel like writing much. If what I wrote above sounds tempered and measured and like it’s coming from a place of proper perspective (I’m not even sure it sounds that way), that doesn’t reflect the way I was feeling last week or for most of the past few months either. My first draft came out pretty negative and I’ve since rewritten most of it. I don’t want to just rant or to elicit gasps at things that seem dysfunctional here through American eyes, of which there are plenty. There’s also so much that is normal and mundanely functional, and I will try to not overlook those too badly.

I’m missing everyone back home and overseas a lot. Big hugs from over here.

Here are those pictures of UCM:

Bom dia, boa tarde, olá, and hello from Chimoio! I'll throw in some regional indigenous language too if we can not worry about correct spelling for a minute--masuera!

As my sister Katie says, I've been quiet lately--on my blog and otherwise--which means I've been busy. She's right, of course; since my arrival in Chimoio in December I've been putting my living space together, figuring out a routine for persisting on about $200 US a month (plenty really), learning my way around the city, meeting as many Mozambicans as possible and trying to keep all their names straight in my head (Pedro/Pida/Paulo/Ana Paula? Ofelio/Augosto/António/Ajape/Osvaldo?), meeting ex-pats, traveling for Christmas, hosting other PCVs for New Year's, and by far the most time-consuming thing: hitting the ground running hard on work at the university. More on that later.

But Katie's only partially right. My silence on my blog can be attributed not just to the fact that I've been busy, but also to the fact that I don't know where to begin to describe Chimoio and what being here is like. Anyone who's lived abroad and tried to catalog the experience knows how quickly the chasm between what-it's-all-like and what-can-be-captured-in-writing grows. It can be discouraging. It calls to mind something Robert Pirsig wrote in his devastatingly insightful Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, the protagonist coaching his son on writing a letter to his mom: "You’re trying to think of what to say and what to say first at the same time and that’s too hard." Totally. There's so much I could write about--my house and home life, the university and work life, the market, the supermarket, what walking down the street is like, greeting people, language, seeing poverty, seeing wealth, PCV culture, Mozambican culture, hiking, weather, nearby PCVs and their sites, hardest and easiest parts, bugs and spiders, health and sickness, money, ... the list goes on. Where to begin?

But then I remember that I have a whole two years to try to capture it. I think I need to follow Pirsig's advice and start small, just someplace, anyplace. My arrival.

My Arrival

The morning following an evening of tough goodbyes to the Moz-21 PCVs destined for other distant parts of the country, the other "Central Region" PCVs and I hopped a plane for Chimoio. As we came down out of the clouds we were treated to our first glimpse of the beautiful and startlingly different topography we would inhabit for two years. Expanses of brooding mountains interspersed with expanses of desolate plains. (Perhaps it was just the cloudiness of that day that calls those particular adjectives to mind.) In some places there would be a mountain peak jutting out of an expanse of plain, just sort of in the middle of nowhere. I liked it. I think we all began to get really excited at that point in the descent. How could you not? One of my favorite things is that the landscape is not quite like any other place I've been, which means someday I'll have all sorts of strong emotions and nostalgia for this place wrapped up in my mind's eye view of those mountains and plains. Like I do for Cuenca, Ecuador.

Anyway, I definitely owe you a picture of the things I just described, and promise to eventually post one.

After this short flight, we arrived in Chimoio for a 3-day conference. (There always seemed to be just one more thing before we could start our 2-year service.) Here are a few of us in the Chimoio airport!:

This room, which is absurdly fancy by Mozambican standards, constitutes almost the entire airport. It's tiny.

Why did we fly to Chimoio instead of driving? Well in part, it's because of a situation that some of you may have read about in the news. Just google "RENAMO". Shortly after the Mozambican civil war ended in the early 1990s, the country has had elections regularly, in which two parties have participated peacefully: FRELIMO and RENAMO. The unfortunate part is that FRELIMO has almost always won the elections, increasingly so, and with increasingly larger margins. Unfortunate, because a slide into a one-party system isn't much of a democracy. Things really came to a head in 2013, a year of local elections, when RENAMO openly refused to participate in the elections (or possibly just some RENAMO candidates--please excuse if I'm using inexact language). Much worse, some RENAMO militants took over dozens of kilometers of the EN-1 in the province of Sofala. The EN-1 is Mozambique's most important roadway and just about the only way to move north-south in the country. The guerrilla militants began shooting. They shoot at cars passing through every day. As you would imagine, it's incredibly dangerous to travel that section of the EN-1. There are deaths constantly. This is tragic, and from a historical perspective, also the most important event in the country since the end of the civil war, at least as far as peace is concerned. The day the violence erupted (I think it was in October?), my host-dad in Namaacha said, hardly believing his eyes, "Acabó a Paz!"

The ruling party, FRELIMO, has set up a military convoy to shuttle cars across that strip en masse at regular intervals, which is your only option if you're willing to risk traveling it. If you have the money, or the backing of the most powerful country on earth like I do, you fly. I can't imagine having a situation like this in one's home country, what that'd be like. The good news for me is that it's all happening far from Chimoio, and things are pretty safe around here. Also, I've heard that very recently, the leadership of both FRELIMO and RENAMO in Maputo agreed to sit down for talks that would include some international observers. Hopefully things have taken a turn for the better. If you're interested, you should really read up on the whole affair. Like any political-military conflict, it's more complicated than a surface-level description can convey, and this one has roots going at least as far back as the civil war.

But let's return to the topic of Chimoio. After three days of more US-Mozambique cultural limbo at the Castelo Branco hotel, a crazy place with hot showers, air conditioning, conference rooms, and food buffets, we PCVs of the Central Region finally said our own goodbyes and headed off to our various sites in the provinces of Manica (cool weather and pretty mountains) and Tete (miserably hot). These goodbyes were probably less difficult than the Maputo ones; a lot of us were able to reunite just weeks later over the holidays.

My House

Finally it was time for my permanent site! The rest of the central crew got into cars and chapas and braced for trips of anywhere from 30 minutes to 8 hours to places with names like Vanduzi, Dombe, Zóbwè... Steven and I, on the other hand, just moved our stuff down the street. We were effectively already at our site. Meet Steven now, of previous blog post fame, my roommate and colleague for the next two years:  It's probably unfair to post a picture of your roommate so early in the morning :) , so let me include these other photos as well--Steven and I on our first day of work! Or not really, I think it was just the first day of work in January; we'd been into the university plenty of times before. What were we commemorating exactly? The first day of work with an expectation that we'd keep coming back every day of the week?

The thumbs-up is ubiquitous in Mozambique. It's a little informal and very versatile. It's great to use with kids. It's not considered corny here. You see it exchanged between even the faux-toughest of teenagers.

As you can see, we're pretty dressed up in these photos. If you think of Africa as a place where everyone roams around barefoot wearing tattered rags, let me dispel that illusion for you. In general, that's more the exception than the rule in both rural and urban areas. If you have any kind of ability to get your hands on nice clothes--more people than you'd expect do because it's sold really cheap here 2nd-hand, shipped in from all over the world--you're expected to dress nicely. Formally. That's especially true for high school teachers, and even more so for university professors. At training they kept telling us it was a question of respect, that it was disrespectful towards everyone else to look poorly put-together if you could at all help it. Mud on your clothes or shoes--unacceptable. Wrinkled shirt--unacceptable. Your shirt needs to be ironed even if you live in the mato with no electricity! They really drove these points home to us in training, but I'm not sure if they apply to just people in positions of stature (like teachers), or if they apply to everyone.

You do see some t-shirts and shorts around here in Chimoio, but mostly it's children and young people wearing that kind of thing. And laborers do wear pretty scruffy-looking clothes when on the job. But mostly, you see men wearing polos and collared shirts, even those of modest means.

Now, without question more severe poverty exists as well, and I don't want to minimize that. There are folks without the resources to get their hands on clothes and especially shoes, and you do see that kind of thing. Often it is the children who end up running around wearing nothing but dirty rags. I am still new here and there is a lot I haven't seen, so I hope the perspective I'm sharing here isn't too distorted or one-sided. I guess my only point in all of this is that culturally, appearance and dress are prioritized in Mozambique more than someone from a U.S. perspective might expect. Changing gears here, I'll say that little by little, I hope to include a lot of pictures of Chimoio, which give better descriptions than I ever could. The thing is though, carrying a camera around out in public is problematic. At best, it's a conspicuous display of some serious wealth, and at worst quickly attracts a lot of overt attention and unwanted requests--although, a lot of the time that's just kids harmlessly wanting you to take their picture. I'll grab some pictures of life in the city as I can, but it's going to take some time.

Getting back to that move-in day back in December--they took us and our luggage down the block from the hotel to what would be our house for the next two years, dropped us off, and then we were on our own. We were happy to finally be so. The house is really a fantastic place to live. Everything I wrote about it previously is true; it has running water and electricity most of the time, and it has amazing fruit trees out back. The house is a huge comfort to come home to every day, and I'm grateful for it. It's gotta be among the fanciest places Mozambican Peace Corps volunteers get to live. I'll close this post with some photos of the house and a promise to post about work and the university next time. Até a próxima! Obrigado por ler! Be well.

Chimoio, Manica Province!! :)

After weeks and weeks of TENSE anticipation, at last I received the decision on my permanent site location, the place where I will be spending the next 2 years: the city of Chimoio, located in the beautiful, mountainous province of Manica! That's me on Peace Corps Volunteer swear-in day in Maputo, pointing to the exact spot I'll be calling home for a long time to come. But I'm getting ahead of myself... It all started at the beginning of November when we PCTs were given a much-needed break from training in Namaacha, and for a period of 5 days, we were scattered to the far corners of Mozambique to visit currently-serving PC Volunteers. Shadow Site Visits. The idea was to get the chance to see and experience the way Volunteers really live at their sites, to pick their brains, and to hopefully return to Namaacha with a better sense of what characteristics we would prefer in our own future permanent sites. With fellow Moz-21er Joe at my side (a fantastic human being), I visited Yuri (another fantastic human being) at his site of Chidenguele in the province of Gaza. Electricity but no running water. Bucket baths and pit latrine. Tight-knit community of friendly teachers. Awesome Mozambican roommate. Stunning beaches. An insanely beautiful night sky. There's a lot to love about Yuri's site, and I began to get very excited for my own permanent site.

Chidenguele, Gaza: We also teamed up with fellow Moz-21ers Sarah and Aleesa to visit their currently-serving PC Volunteer, Taylor. A combined shadow site visit, basically. Unlike Yuri, who teaches at Chidenguele's high school, Taylor is a health volunteer. She lives in Quissico, Inhambane province, and although I don't have pictures of the area surrounding her house in her site, it's just ridiculously beautiful.

Quissico, Inhambane: After these shadow site visits, the next thing was to return to training in Namaacha and get ready for my permanent site placement interview. What had I learned about what I wanted in a site? I didn't know. I could see myself being happy at a site like Yuri's or Taylor's, but I could see myself being happy at just about any site. The beaches near Chidenguele and Quissico were nice, but mountains are nice too. I could enjoy being within a few hours of a city with a supermarket that sells cheese imported from South Africa (like the city of Xai-Xai for Yuri and Taylor), but I could also enjoy learning to live deprived of such things for two years. I was getting pretty excited about living on my own without running water and with insects and lizards always in the house (in my time at Yuri's and Taylor's sites I saw that these things are really no big deal), but I figured that that reality was pretty much a given wherever I got placed. And how much would my stated preferences even matter? You hear plenty of stories of PC-Moz Volunteers getting none of the things they requested in their permanent sites anyway. We were supposed to come to our permanent site placement interviews with a preferences questionnaire completed. The questionnaire included things like this: - Rank in order your preference for teaching the following subjects: English, Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry, Biology, ...

- Would you be willing to have a site mate (other PC Volunteer in your same town)? Roommate?

- On a scale of 1 to 5, how rural or urban a site would you like?

- If you had a magic wand to grant you one single thing at your permanent site, what would it be?

Among the Moz-21 PC trainees, there was much talk and deliberation about what everyone would put down. Some people enthusiastically lobbied for an as-rustic-as-possible site, others pleaded for amenities. The magic wand question was especially interesting; answers were as varied as beaches, mountains, fruit trees, nearby hiking, nearby swimming, electricity, no electricity, Mozambican roommate, cold weather, north and south parts of the country. But what could I put down? The things I wanted in a site--to feel like my work matters, and to not be separated from the people I had gotten close to during training--those things weren't anywhere on that questionnaire. I didn't see any way that that form could help me with what mattered to me. I resolved to leave the questionnaire blank and throw my fate into the wind, the way we all did at the very beginning of this journey when we applied to be sent to any far corner of the world. Then, a spark. My friend Steven returned from his shadow site visit with a face full of excitement, and pulled me aside at CORE the first day we were back at training. He had just returned from an amazing place, he said. A place where the weather is cool, where there is beautiful hiking within walking distance, where there is awesome wildlife in the region (elephants!). A place that not only has supermarkets that sell cheese, but is home to Mozambique's only small, but promising, budding dairy industry! A place where Peace Corps lodges its Volunteers in a fantastic house with electricity, running water, a garden, and a backyard that is almost too good to be true--grapevines and mango trees, lychees and passion fruit, all there for the picking. A place where other Volunteers are always passing through. A place with fully-stocked fresh food markets, where you can get a solid plate of rice and beans for just 20 MT. A place home to a regional market with one of the biggest and best capulana selections in the entire country. A place so universally liked by visiting PCVs that 3rd-year-extendees come to live there when given the choice of living anywhere in the country. A city, but a small city that has a comfortable and manageable feel. Chimoio. But more important than any of that, Steven told me about how Chimoio is home to a university with the only engineering programs in the entire country outside of the capital city of Maputo. The Universidade Católica de Moçambique, or UCM for short. The only spot in the country, it turns out, where Peace Corps has Volunteers working as college professors instead of just your standard high school teachers. Steven told me about how he and the PCV he visited (Anna Derby) hung out with some UCM students while he was there and about how they had long, excellent conversations together. He told me about how bright these students are and about how they actually talk about wanting to use the education they're receiving to build and develop their country. (The opportunity to go to college in Mozambique is extremely rare.) On top of ALL of that, Steven told me that UCM is launching a brand-new electrical engineering major (my background) in 2014 and a brand-new mechanical engineering major (his background) in 2015. You can only imagine how much my excitement was building. Steven told me that UCM loves the Peace Corps Volunteers they have now and have had in the past, and that the university has been begging to be sent more. He told me that Anna told him only one PCV from our group (Moz 21) was slated to go to Chimoio to teach at the university, but that maybe we could lobby for an additional one given how much the university wanted it and given the symmetry of sending both an ME and an EE to develop the two new respective engineering departments. Knowing that our two backgrounds would be perfect for the site, Steven came to me and wanted to know if I liked the sound of all of this before we started to make our case for it. I was just floored. It all sounded amazing to me. I thought of the amount of positive impact a team of two young, enthusiastic American engineering professors could have on a country with a real need for industry, the amount of impact we could have given the supply of intelligent and focused students coming through the doors. We talked about how together, we could build a culture of positivity and excellence within the engineering department, about how we could connect these bright kids with the resources they deserve, the resources that will allow them to do great things in their country. Everything seemed perfectly aligned, as if my five years working as an engineer and two working as a teacher had all been preparing me for this, had all been to get me to this point. I knew Chimoio would be a dream-come-true if it could become my site. I decided I would try as hard as I could to get a post at UCM. So instead of leaving my questionnaire blank, I filled out only one part--the magic wand section. My magic wand section said effectively this: "Send me to UCM in Chimoio." That, along with the best rationale I could come up with for why doing so would be a good move for Peace Corps. I made sure to leave everything else on the form blank, not wanting to dilute my request with any other secondary requests. In my interview with the site placement staff (I believe the date was Monday, November 11th), I continued to pursue this single-minded strategy of being sent to UCM. The interviewer asked me about my site visit to Chidenguele, wanting to know what things I liked and didn't like, but I told him I only wanted to talk about me going to Chimoio. But crushingly, he told me that Peace Corps wasn't sending anyone from Moz-21 to Chimoio, that the vacant UCM position was going to a 3rd-year-extendee who would be moving to Chimoio. I asked him instead that I be sent to a different university to teach engineering, to which he replied that Peace Corps didn't work with any other university in the country, that I would be going to a high school. I left the interview feeling like things could not have possibly gone worse, but that at least I had tried. It was a reminder that the decision was never anyone else's but Peace Corps'. After getting so excited at the prospect of being a university professor, I tried to ratchet my expectations back down to where they had been previously. I tried to remember that my site would be exciting no matter what. And that's true. But what happened next blew apart any expectation-setting I tried to do for myself in those days. What happened next would be described as a miracle by all but the most frigid, unblinking rationalist. After 2 days of agony and 1 day of finally being at peace with things, my wait for site placement announcements--and everyone else's--was finally over. The Peace Corps staff assembled all 51 of us and tried in advance to keep expectations and emotions under control--a ludicrous proposition. The Country Director (everyone's boss in Moz) explained that based on his experience, roughly 1/3 of us would be miserable--without basis--upon receiving our site placements, roughly 1/3 of us would be ecstatic--again without basis--upon receiving our site placements, and that only the remaining 1/3 of the group would get it right by reacting with measured calm and keeping things in perspective. In his experience, hindsight shows PC trainees to be lousy at predicting how much they're going to like their own site. The staff walked us outside to a nearby soccer blacktop where they had drawn an enormous map of Mozambique. The idea was that we would receive our site placement packet and go stand at the place we'd be living for the next 2 years. The drama of seeing just how close or far away your friends have been placed lent a certain sensory-realness to the whole exercise. This country literally takes days to traverse without an airplane. No matter where you get placed, at least 50% of the other volunteers will be basically too far away to ever realistically visit. That's the kind of thing that I was thinking about, but there was plenty to be anxious about as far as site specifics go, too. There was also plenty to be excited about. So yeah, it was an intense moment to be sure. We got our site placement packets, and I was definitely in the 1/3 that reacted with unhinged ecstasy. Chimoio. It was impossible, but there it was on the page. The site placement staff decided at the last minute that what the heck, they would send just one more volunteer to UCM in Chimoio, what could it hurt. I walked to my spot on the map in a daze. There was Steven sharing my spot, with his big goofy grin, a better roommate and site mate impossible to find. I looked around in a dream-like trance. There was Fei, just steps from me on a map the size of an Olympic swimming pool, impossibly. Fei, the thought of whom being placed far away from had been more difficult than any other. 3-4 hours away by chapa in a country where the average travel time between any given two volunteers is more like 20 hours. I couldn't believe it. Some of my very favorite people all around me--Carly and Aleesa, also both in Manica. More favorites just a jump away up in Tete and Zambezia. I couldn't believe any of it. Like anyone receiving news on this level of insane awesomeness, I spent the next couple of weeks on cloud nine and simultaneously being afraid that it wasn't real and that there had been some mistake that would be corrected and then everything would disappear. But it hasn't disappeared, and nor has my joy. Like any other, my site will present its challenges to be sure, and maybe a small part of me will one day wistfully think back to the Country Director's warning of the misguided, overenthusiastic 1/3 at site placement announcements. But I don't really even believe that. The truth is that I have just simply won the lottery by every conceivable metric and in every way imaginable. I don't see how this site placement could be any better. The work, the people, the area--it's all there. Many weeks have passed and I still have not gotten over what a crazy lucky hand I drew. I probably never will. We are in the realm of things far beyond what is statistically reasonable, and I don't know what else to do besides throw up my hands and be grateful. I don't deserve any of it but I am so happy to be here and to have been given the ultimate high-five from the universe.

Every once in awhile, I think about the fact that a lot of people back home in the U.S. feel sorry for me to be living here in Africa, or at least think that I'm making some kind of sacrifice to be here and should be the subject of condolences or even pity for what I'm going through, living in a tough place and all that. From the perspective of actually being here, that train of thinking is just amazing to me and seems almost impossible to believe. It's baffling to think how anyone could confuse this wonderful experience with suffering, or with something to be avoided. How could anyone not want to be here?? Sometimes it's rewarding, sometimes it's beautiful, and sometimes it's just plain fun--there is a whole color palette of different shades of joy this trip has to offer, from the profound to the light and frivolous. Rather than longing to be comfortable in the U.S., the thought of being sent home (for a medical issue or program closing or whatever) terrifies me.

One of those moments of reflection took place for me a few weeks ago in Namaacha at the top of a mountain. A couple friends and I were actually laughing out loud at the very idea of being pitied for living in Africa. We had just hiked to the summit of the mountain that holds the point where the borders of three countries come together--Mozambique, Swaziland, and South Africa. From there you can look for miles and miles into any of the three countries, and there's no avoiding the realization of just how arbitrary and senseless borders and country divisions are. The view to the Mozambique side is essentially a view of Namaacha, far below. This was the second trip up to as três fronteiras for me, and what was special about this time was that we left at 3:30 in the morning to catch the sunrise from the mountain top! :)

Staggeringly beautiful. I'll let the pictures below speak for themselves. The sun and the mist interacted in a way to create a variety of visual effects I'd not previously thought possible. Among the group of us up at the top of that mountain, there was nothing but a giddy, carefree happiness and gratitude to be alive and to be living in Mozambique. We stayed up there for hours and hours, not wanting to go back down. When I finally did go back down, what followed for me was an unforgettable afternoon back in Namaacha.

For someone in my shoes, life in Africa is many things, but mostly it is a joyride through some of the most wonderful physical, spiritual, and emotional pleasures this world has to offer. Being here is not a hard choice :)

-2 chickens in Namaacha.

On Wednesday, I finally brought to a close my unfinished business of killing a chicken. My family bought 10 chickens (frangos) to kill and prepare for the party we're having today (Saturday), which is being held in honor of my sister Lalita's 20th birthday. I killed and de-feathered two of them.

Mostly I just tried to get through it. The look on my face below is one of grim concentration. My least favorite part was picking up the chicken and pinning its legs and wings down under my feet. But my sisters Aida and Lalita coached me through everything. They made fun of my ineptitude and trepidation a little bit, but also understood why killing something for the first time was sort of a big deal, which I appreciated.

The photos below are just a little bit gory, just a heads up. Big thanks to my 8-year-old-brother photographer, Fedinho! The very last picture shows us dipping the dead chickens in boiling water so the feathers and feet skin can be pulled off easily--standard operating procedure.

This is long overdue. I realize many of you may be curious about what Namaacha itself looks like!

For starters, here’s my house:

Side-view of my homestay house in Namaacha. The little structure on the right is where we cook.

The fence in the foreground is the edge of my family's backyard. The barbed wire fence is the Mozambique-Swaziland border!

I live in the neighborhood Frontiera, which is basically the ritzy part of town. Here are a bunch more pictures, many taken in Frontiera but not all. Hope you enjoy, and make sure to read the captions.

|

But wait, what about these people?

But wait, what about these people?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed